By GARY GEDDES

When I came out of the Internet café in a cavernous basement onto the dirt road in downtown Hargeisa, a small creature brushed my leg and shuffled ahead. It was a baboon, sidling toward a small table of fruit attended by a middle-aged woman. Without turning, the baboon reached over its head and plucked a banana from the table, skipped 10 feet out of range and rested on its buttocks to enjoy the fruit, carefully peeling back the skin in three perfect sections, which it chucked over its shoulder into the street. A quiet scene, obviously repeated so often that the victimized merchant didn’t even protest. This was not the Somalia of piracy, kidnapping, executions, warring militias and famine the world is now hearing about daily.

The news from Somalia is distressing beyond words, thousands starving, those still mobile shuffling toward refugee camps inside Kenya. The tally of children dead from starvation and disease is 29,000 and mounting. Thousands more are being detained by the radical Islamic group known as al-Shabaab (meaning “the Youth” and modelled after the Taliban), which is anxious not to be outflanked by foreign aid agencies but has little to offer in the way of supplies.

The news from Somalia is distressing beyond words, thousands starving, those still mobile shuffling toward refugee camps inside Kenya. The tally of children dead from starvation and disease is 29,000 and mounting. Thousands more are being detained by the radical Islamic group known as al-Shabaab (meaning “the Youth” and modelled after the Taliban), which is anxious not to be outflanked by foreign aid agencies but has little to offer in the way of supplies.

While everything possible should be done to bring food, water and medical aid to these desperate refugees and internally displaced people, besieged by both man and nature, it’s worth pausing to think about the northern Republic of Somaliland, an oasis of stability in the midst of mayhem and chaos.

Somaliland has just completed 20 years of peaceful co-existence as an independent nation, with elected representatives, schools and a functioning judicial system. The northern region was under British rule until it gained independence in 1960 but quickly joined the greater Somalia, thinking, perhaps, that there might be strength in numbers and more bargaining capacity with the great powers.

This proved true, briefly, until Siad Barre overthrew the elected government, reintroduced clan-based privileges and alliances, tried to play off the Russians against the Americans, and began a disastrous war to regain the Ogaden grazing lands ceded by the British to Ethiopia and still a major bone of contention.

When I was in Hargeisa, the capital, in the spring of 2009, it was recovering from three bomb attacks by radical outsiders trying to destabilize the country. But the streets were safe, the markets bustling and a major poetry event and a Festival of the Camel were in progress. Much of the GDP was provided by relatives abroad, but the country was, by African standards, a model state, with the rights of women and children slowly improving. While the international community still refuses to recognize this new state, it’s worth remembering, as Mark Bradbury reminds us in Becoming Somaliland, that it’s more embracing of fairness and liberty than most of its African and Persian Gulf neighbours.

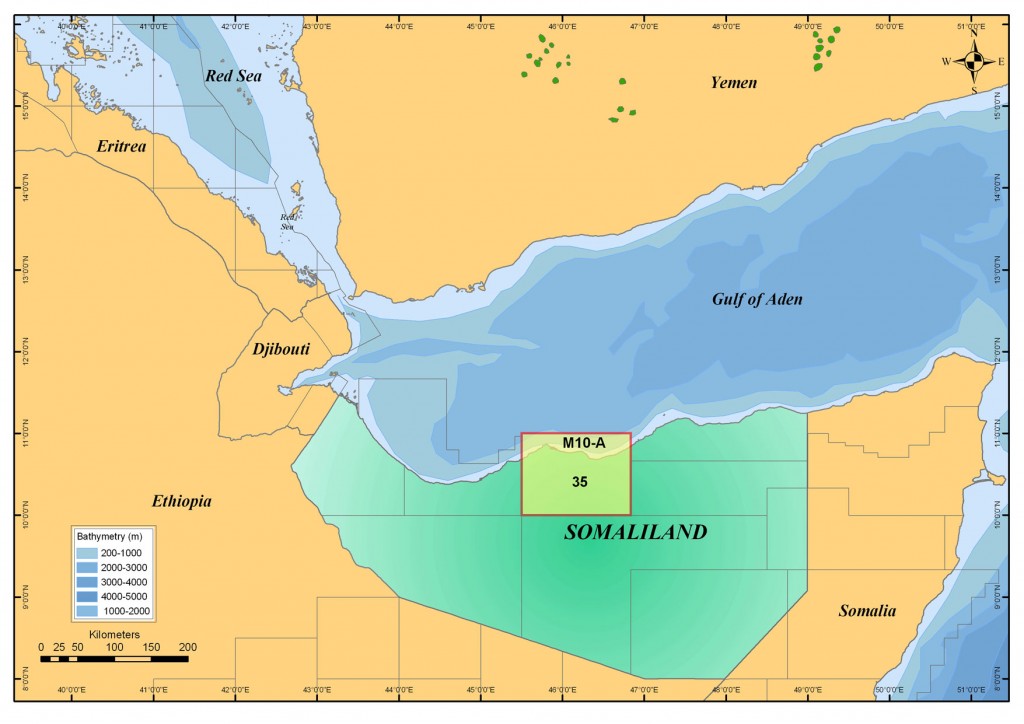

Many nations that might lead the way in recognizing Somaliland have been reluctant to encourage separatist movements. It’s not difficult to imagine how Russians, Americans, Chinese and even Canadians might have viewed this not-quite-vibrant upstart throwing off the shackles of a brutal dictatorship. Hargeisa had been ignored and finally bombed by Siad Barre’s regime, suffering more than 50,000 casualties. Humanitarian workers were thrown into jail and writers driven into exile or rebellion. During my trip to the coastal city of Berbera, with two armed guards to keep me company, I saw an obsolete tank abandoned beside the road, its barrel trained on some invisible enemy in the sky, and in the harbour, the rusting hulks of sunken ships rested at improbable angles in the sky-blue waters of the Gulf of Aden.

African nations, their borders arbitrarily carved by European colonial powers, were equally reluctant to encourage breakaway sentiments in the political units they had inherited, although tribes and ethnic groups had been torn asunder by the political and economic ambitions of foreigners, many of whom are still key players in the scramble for African loot. But now that South Sudan has achieved independence through a nationwide referendum, this may pave the way for Somaliland to make its own case in the international arena.

It would be great if Canada took the initiative and made the first move in this direction, a long overdue act of largesse to compensate for the travesties of the 1993 Somalia affair, when Canadian soldiers tortured and murdered a Somalia teenager named Shidane Arone. But that’s another story.

Gary Geddes is the author of Drink the Bitter Root: A Writer’s Search for Justice and Redemption in Africa.